Photographic Intentions

April 26, 2017

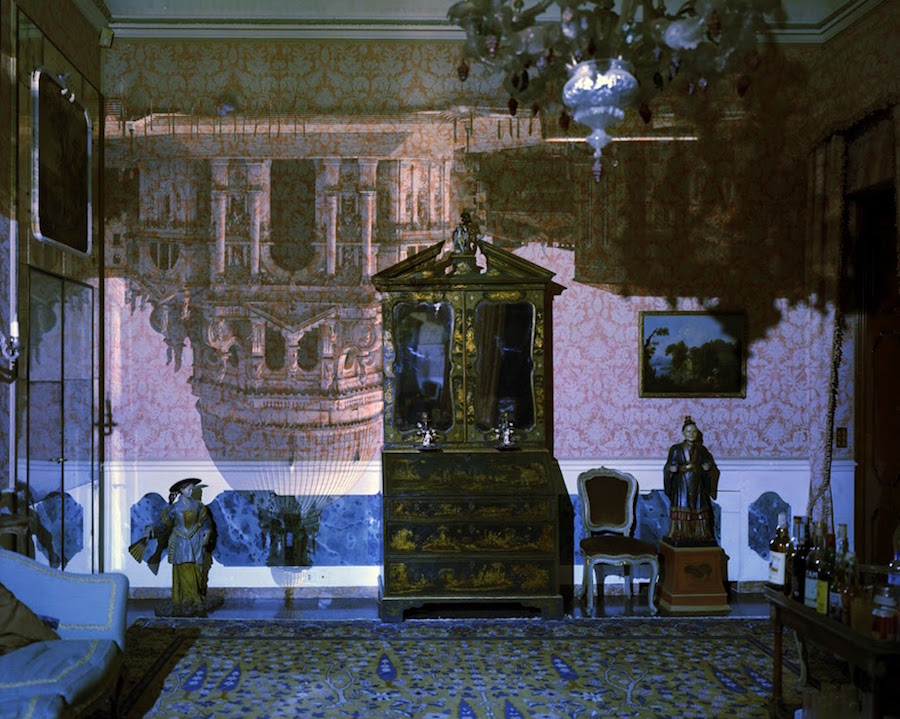

Fine art photographer Abelardo Morell uses the camera obscura technique combined with long exposure times to create haunting images of rare beauty. This photograph was taken in Venice in 2006. He is represented by Edwynn Houk Gallery of NY

It’s next time again. I’ve been thinking a lot about photography lately. Most of this is from the research I’ve done for a speech I’ll be giving to the Public Relations Society of America at the end of this month in, Corning, New York, at their North East Chapter annual conference. I was stopped in my tracks the other day by a simple statement of a profound idea from Elizabeth Edwards, a British scholar, who was discussing the history of photography. She said, “Photographs always contain more than the photographer intended.” As someone who spends a great deal of my life investing meaning into photographs in the films I make I felt the hair on the back of my neck horripilate as I thought about this amazing idea.

Dutch Creative Director Eric Kessels visualizes the one day upload to Flickr with 350,000 printed photos piled into a gallery. Photo courtesy Eric Kessels, 2011.

To ponder this concept you really have to step back out of the flow of what you witness every day. It is pretty much beyond the comprehension of any normal person. Maybe some of you can make sense out of this but I know it is far beyond my ability to fathom. Today 1.3 billion images will be uploaded to the internet. What?! I don’t have any clue what this means. I can maybe understand a smaller number thanks to a remarkable exhibition a few years ago by a very smart artist, Dutch Creative Director, Eric Kessels, who decided to print out one day’s upload to the photography site Flickr. This turned out to be a staggering (but minuscule in comparison) 35,000 images and he did installations in various venues, (churches, galleries, museums) of all these pictures just strewn about in giant piles so you could actually visualize how many images this really represents.

35,000 is a number I think I can understand. 1.3 billion I cannot. Today on Instagram alone it will be 80 million images uploaded generating 3.5 billion “likes” per day. Are you kidding me? I just cannot seem to wrap my mind around these gargantuan numbers and I have even more trouble trying to figure out what this means to the way we see the world? Do you share my astonishment?

The Daguerrotype (left) is a one of a kind image with pinpoint clarity. By the 1860’s photography had penetrated every aspect of society including politics. Photos by the Daguerreotype Society and the Library of Congress

So lets turn the telescope around and see if that helps at all. It doesn’t really help but, it is fun to try to imagine. I can’t quite do it, but I try to imagine a world before photography. You maybe think, like I did, that photography was invented by Louis Daguerre in 1838. We all know his name from the haunting Daguerreotypes that illustrate our American Civil War. Daguerre is a fascinating guy and it turns out the reason we know his name is because his first step was to take his invention to the French government. He wanted a government pension and he thought the French officials should treat his scientific discovery as the earth shattering big deal that he knew it would become. His sales pitch to the French Academy of Science and the French Academy of Fine Arts worked. He got his pension and the French embraced photography through official channels long before other countries got on board.

View from the Window at Le Gras by Nicéphore Niépce was made in 1826. It may be the world’s oldest surviving photograph. It has the feel of a cubist painting. Niépce called his work heliography or “sun painting.” Photo now in the collection of Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin

I was talking about this with my dear friend Abe Frajndlich (who is a great photographer) and he corrected me before I could finish saying Daguerreotype. He pointed me to another French innovator, Nicéphore Niépce, who made a photograph eleven years before Daguerre. Turns out they worked together but Niépce died just a few years after this image was created and he never got to see the impact of all his innovative work. This image has the dreamy look of a cubist painting. In our photo-saturated brains this image “clicks” for very few of us. But here is the thing, photography from Niépce and Daguerre were unique, they were one of a kind. They were like individual paintings. One offs. It took the Brits to develop the negative and paper printing technologies that allowed for the mass dissemination of photography. It is one of those combination of technology stories where powerful innovations collide, obtain critical mass, blows up the world and changes life as we know it.

William Fox Talbot was one of the British “gentleman-scientist” innovators who pioneered the paper and negative technology which was essential for transforming photography from a one-of-a-kind method like the Daguerreotype into a mass medium. Photo of Talbot outside his studio is from 1853.

The British technology took one negative and made lots of copies. Combine this technology with new advances in printing and you get the explosion of imagery that transformed our worlds. Another scholar, Simon Schaefer from the University of Oxford explained that photography was like the “big data” of the 1850’s. He said that by the 1850’s photography had “penetrated into every aspect of society.” This means everything; Science, Medicine, Family, Criminal Justice, Entertainment, all of these and more, forever transformed in a period of about 15 years. What a statement! What is the equivalent for us? Probably the cell phone or the internet. Hard to imagine what we did before those showed up as ubiquitous essentials in our lives.

The KODAK box camera reminds us that photography is based on the age old technique of the camera obscura. In 1889 you could buy this camera pre-loaded with film for 100 pictures for twenty five dollars. Photo courtesy Smithsonian Institution.

One of the first early uses of photography was portraiture. In the 1840’s a portrait cost £300 (about $500). This was a lot of money in 1840. By 1900, thanks to KODAK you could buy a camera and 100 pictures for twenty-five bucks. Their simple box camera reminds me of an revelation I should have had years ago. Why didn’t I realize where the word for what we call a camera comes from? I’m embarrassed to say I only just put together that the Italian word for “room” is, of course, camera.

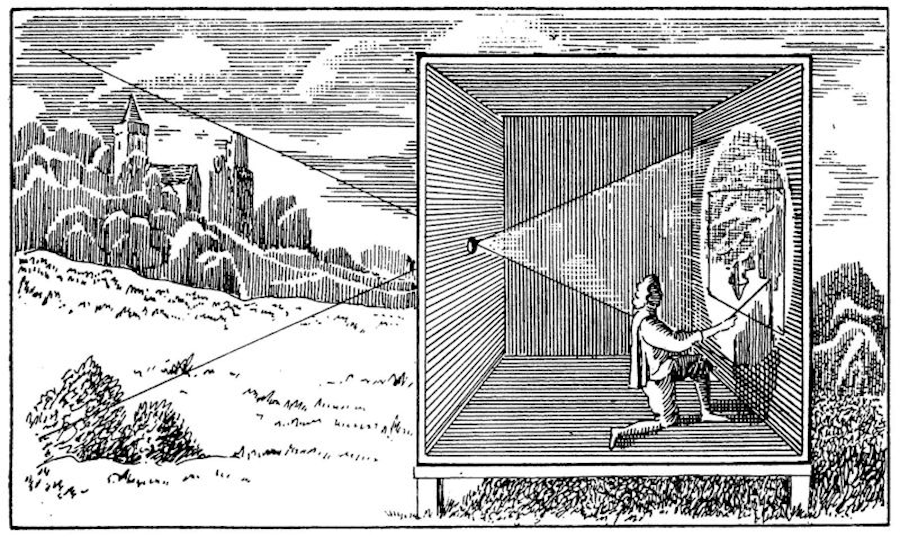

The camera obscura gives the camera its name. Camera means “room” in Italian. Engraving shows an artist tracing the flattened image of a landscape. Artists from Leonardo to Caneletto employed the technique.

The box (or the room) is the Camera Obscura. This is the natural phenomenon where, under the right lighting conditions, a pinhole in a wall or blacked out window will project an upside down image on the far wall. KODAK’s box is actually a very small room refining the same technique with a lens to make the image sharper. The challenge was to find a way to preserve the image through a chemical process. This was the elusive miracle engineered by the early innovators like Niépce and Daguerre. By 1900 the once astonishing had become everyday. Leave it to a brilliant photographer like Abelardo Morell (above) to revitalize the camera obscura technique with magical fine art photographs which express the wonderment all over again. He is represented by Edwynn Houk Gallery of NY.

Magnum photographer Eugene Richards took this now iconic photograph of an impoverished young girl playing with a dolls head in Arkansas over forty years ago. Photo courtesy of the Artist

In further researching my presentation I came across the work of Eugene Richards who is a photo journalist and works for Magnum. His work is like fine art to me. He is quoted in the New York Times talking about the deluge of images we navigate every day. “I’m sure people are getting fed up. In my own head, there’s a huge over-saturation of images. For a long time I never expected myself to feel tired of seeing so much.”

So what would you trade? Would you rather have the 80 million photographs uploaded to Instagram today or one exquisite Eugene Richards photograph like his iconic image of an impoverished young girl holding the head of a doll? For collectors, they fully realize the genius of the quote above about the photograph always containing more than the photographer intended. When you live with a great photograph, like any work of art, you hopefully see and experience new revelations as the image becomes a part of your life.

Eugene Richards is articulate and enigmatic about this. He used the image of the little girl with the doll as the cover of the book he did about his work about poverty in Arkansas but has become uncomfortable about the meanings read into the photograph as it has become famous. He said, “It’s still not my favorite picture. And it embarrasses me because I never intended it to be an iconic image. I’ve come to dislike — it sounds strange — iconic images because they hide so much. Eddie Adams’s Saigon execution picture is a naturally great antiwar statement, but it wasn’t his intention.”

Until next time. . .

12 Comments

Dear Tomasso,

Your discussion of daguerreotypes went straight to the heart so to speak. One of my first jobs at the Historical Society centered on bringing order to the institution’s photographic collections. I was given the exalted title of “Picture Specialist.” That position gave me my first real look at daguerreotypes and other cased images.

Having read The House of Seven Gables, I was familiar with the term. Given the mood of Hawthorne’s gothic novel I came to imagine daguerreotypes as something dark and mysterious. Despite my work with the actual images, I still cannot fully separate myself from that mental image. I don’t know if it was it was the power of the novel or simply the strangeness of the medium’s name that sometimes still obscures the reality I discovered when I began to review and catalog the extraordinary collection of cased images at WRHS.

I simply found them fascinating. The highly reflective surface which dictates they be viewed at a specific angle and light is intriguing. The fact that each (unless it is a purposeful copy of another) is unique was compelling to me even before the onslaught of digital images. Their total lack of granularity gives them a clarity and depth unlike any other photographic image — they do not pixilate when viewed under a magnifying class or even a microscope. A good friend (who is a noted collector), contends that one can sometimes see the reflection of the camera and photographer in the eye of the subject. I’ve not been able to do so, but I do trust his expertise and judgement. I’ll keep on looking!

Adding delight to the process was the fact that daguerreotypes, like ambrotypes and some early tintypes, are stored/preserved in a case, most usually wood and leather, but at times, made of an early thermoplastic material. The cases have intricate designs, reflective of the style and taste of the era and, of course, the subject or purchaser of the image. Many of these are well described in Floyd and Marion Rinhart’s book, American Miniature Case Art. So, one finds art within art.

As you might sense, I was (and remain) smitten despite Hawthorne, Holgrave, Phoebe, and Judge Pyncheon. Daguerrian images may “…dodge away from the eye..,” but I don’t find them “…hard and stern.”

I will close by noting that Boston was home to two of the finest daguerreotypists in the nation, Josiah Hawes and Albert Southworth. There’s a wonderful older catalog of an exhibit of their work published by David Godine, The Spirit of Fact: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth and Hawes. I have a copy that I’ll share with you when you are back in Boston. Mille grazie for reviving some good memories of my early years at WRHS!

John

Horripilate. This is why I love you. As a contributor to the daily visual mayhem and glory of Instagram, let me just say that I am fully aware that my images rise and fall in an instant. Hence the name Instagram. Viewers are free to enjoy or ignore my visual journey. Like all art, one must do it for oneself – not for others. Here’s to too many photos in the world and the truly great ones, as always, rising to the top. XO, Cosima

Dearest Tom

Thank you yet again

We are reading your piece aloud in front of Linda Butler’s photo of Kay Williams dining table. The wonderful images of Kay in mirrors, and we learn more and more as we live with it.

THANK YOU. MLS AND JKS

Hi Tom – so great to read your blog. I think photography is more important than ever as most of the daily communication via Facebook, Instagram etc. is accompanied by images – sometimes its even an image alone. Mobile phones play a crucial role. One gets overwhelmed yes, but then we are also touched when an image hits us and meets our thoughts and keeps us occupied for a long time. There are images we never forget and Egene Richards work is just one excellent example. It strikes me that the images that touch us are about the “other” – they transport something which stands before the photographer – with the image becoming his voice. These images tell us about places, circumstances, communities,culture,politics and the individuals portrayed. I see a fundamental difference between these types of images and those that we see posted every day as those ones are more about the “self”. How much difference does it make to the human condition to see selfies and images of what someone ate for breakfast? In great photographic works I have never seen an obsession with the self.

Another great blog Tom! Up until quite recently I dismissed photography mostly because I the shows I went to see on this art form did not speak to me. Then one day while visiting the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh I stumbled on a small exhibition entitled “Daguerreotype to Digital- a history of photography”. Suddenly I had another perspective, and a new found appreciation for a growing art form. Thank you Tom for adding to my archive of information and for enriching my life tenfold.

Tom–To read your thoughts, on anything really, uninterrupted here is a good thing. Innovations in photography and access to those innovations are ideas that need articulate decoding. At a time when imagery=communication, you help understand the new baseline and one’s intentional position on it. What do I mean and what do you think I mean are equally useful when wordless images are contending for the lingua franca. I appreciate the photos you selected to illustrate your points. Will be following you, wherever. Il bocca al lupo a Corning. Grazie mille

Tom – thank you for taking us back to the beginnings of photography. Your blog reminds me of an experience many years ago when I was writing about the early short films of D.W. Griffith and found myself unaccountably moved by their imagery. An aesthetic mentor of mine said, “You’ve discovered the incomparable power of the original, the thing never been seen this way before.” My favorite all-time photograph has always been the first selfie: Robert Cornelius’s famous self-portrait taken in Philadelphia in 1839, well before the golden age of the daguerreotype, The exposure took more than a minute, and the complex immediacy of the subject’s presence, indeed his spirit, has rarely been equalled in any medium, including painting and sculpture. You’ll see what I mean if you go to: https://publicdomainreview.org/collections/robert-cornelius-self-portrait-the-first-ever-selfie-1839/

Photographs speak their piece of the truth and which cannot be fully negated by words. That’s part of their value and power in civil society.

The proliferation of images is maybe a bit daunting, but I find it also liberating. It’s wonderful to think of so much of the world empowered by the smartphone to communicate so fluidly with images. It’s like humanity was given a second, vivid language. The more visually literate the world becomes, the more the world will value the images that rise above the conversation and rise to poetry.

Dear Tommaso,

Wow, that image of the girl on a stack/mass/cargo load of images is amazing. The numbers you quote are amazing. The idea of shared images, and maybe because of that shared rare image, reinforcement of values, such as the little girl napalm victim in VietNam, or the enigmatic woman with green eyes in Afghanistan, or a slaughtered lion with a hunter who represents everything wrong with social privilege standing over it with is gun. We,share images with the unintended messages tucked into them, which are the grounding of our own expectations, values, hopes and dreams.

As a girl, I always wanted the mail to contain that unexpected surprise valentine from a secret admirer. Now there is almost no mail, and yet ,the expectation transfers to email and Facebook, that someone will say “I love you, I understand you, I agree with you.”

Lately we share anger, horror, frustration and political distress. We share fear for the future of the planet. You don’t care about air pollution if you are willing to blow up the world. The images pile up. I got a copy of the “blue marble” of earth from outer space, to put on my protest poster for the pro-science march last weekend. The guy at the photo shop knew how to google and download the image in a few seconds, and only charged me $6 for an 8×10 copy. My sign said “there is no Planet B, good stewards use science and truth.”

I love the image you put of the poor little black girl, hugging her doll. My immediate response was to think of a photo going around in the doctors’ webpages, of a little white girl holding a black doll. The white store employee asked her if she wouldn’t want a doll that looked like her? She responds with full enthusiasm that this doll is EXACTLY like her, because both the doll and she are growing up to be doctors. I love that image, hat hope, that failure to see limits and that fabulous color-blindness of the child. I find it reversed and told through a glass darkly in the image of the dark child holding the blonde doll’s head. And I wonder who decapitated the doll, and I think about Marie Antoinette, and the whole problem of monarchy, some other order or class having more dignity or respect, and money and power, and the oligarchic rip-off happening now. I love your line about what is unintended in a photograph, and I will keep thinking about that. Thank you!

Tom, your continuous questioning of why and how; followed by the research helps expand our knowledge, without the effort you expend. Thank you.

Wow ,what beautiful and profound images.Love seeing these.

best, sandra